Lossy floating point compression by mantissa truncation

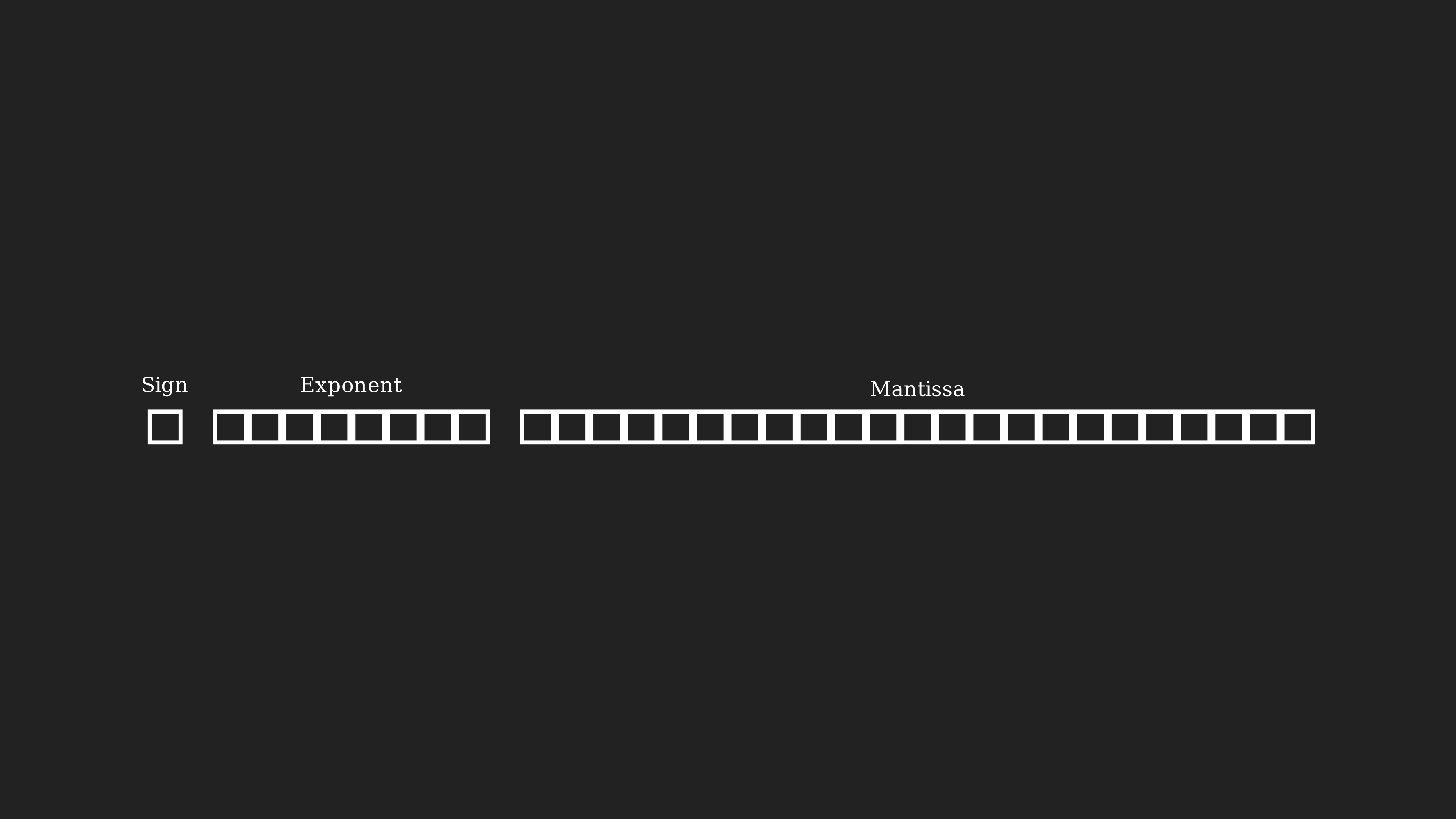

The majority of computing architectures support floating point computation that comply with the IEEE-754 standard. For 32 bit floating point numbers, this standard states that floating point numbers are composed of 1 sign bit, 8 exponent bits, and 23 mantissa bits.

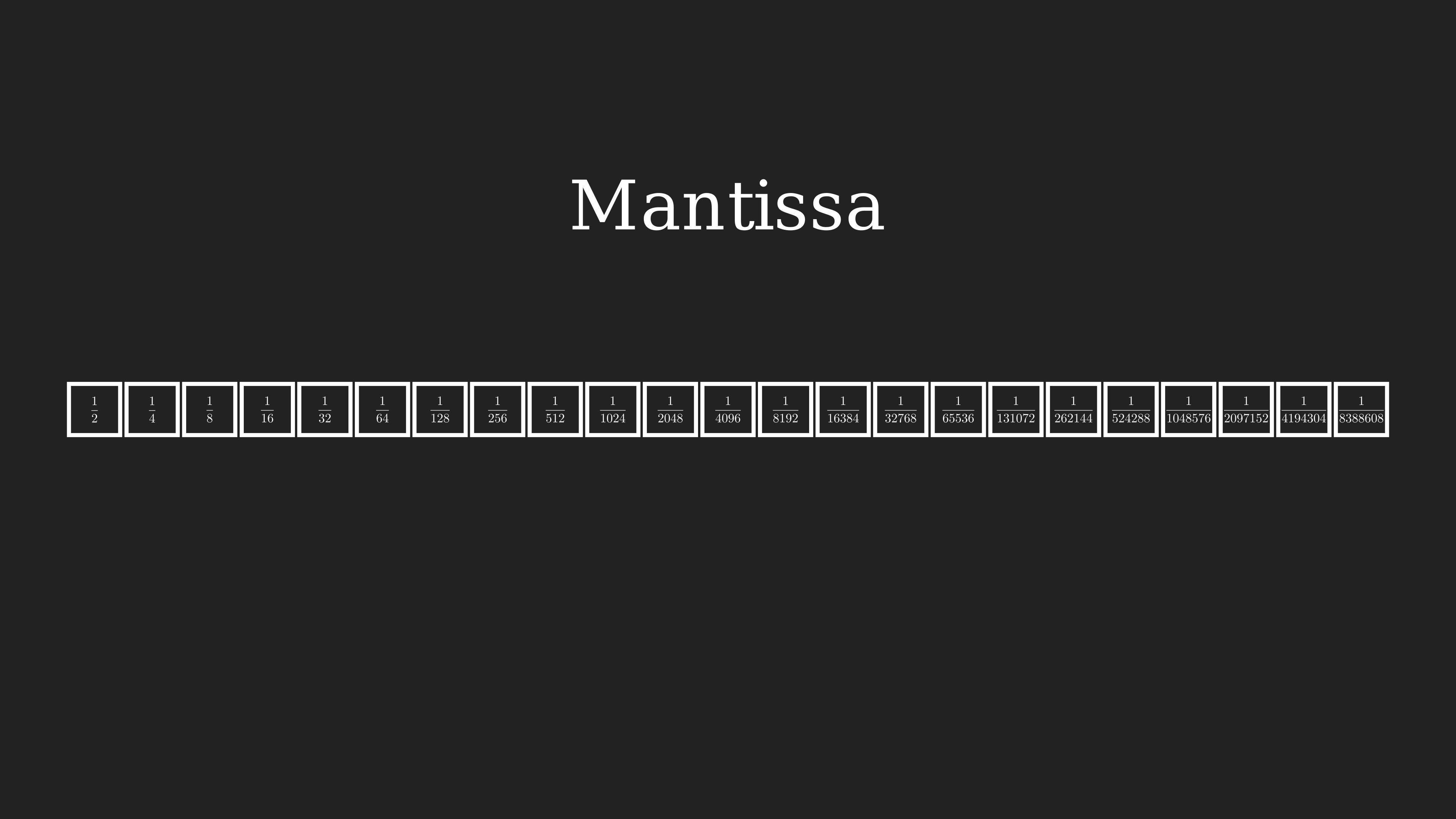

The sign bit stores the sign of the float (positive or negative), the exponent stores the scale of the float in and the mantissa bit stores the digits of the float. The mantissa stores digits in base 2, where each bit represents the value of the float

This is also what causes floating point rounding errors, because not all decimal numbers can be represented in

Mantissa truncation implementation

For a low precision application, the least significant digits of the floating point mantissa could be truncated in order to save space in disk. In c++ this could look like this

float lossy_compression(float value, size_t n) {

/*

* applies a bitmask to zero out last n bits of the mantissa

*/

assert(n < 24);

union {

float f;

uint32_t b;

} u = {value};

// first bit is a sign bit

// next 8 bits are the exponent

// last 23 bits are the mantissa

uint32_t bitmask = UINT32_MAX << n;

// UINT32_MAX = 1 11111111 11111111111111111111111

// bit shifting left by n sets the last n bits of the mantissa to 0 (as long as n < 24)

u.b &= bitmask;

return u.f;

}

however, the actual data is still stored in a 32 bit float, so for actual disk storage gains we would need to "pack" entire buffers of floating point data.

std::vector<uint8_t> pack_n_bits(std::vector<float> &data, size_t n) {

/*

* Removes the last n bits from the end of each float and packs them into a buffer

*/

std::vector<uint8_t> packedData;

uint64_t bitBuffer = 0;

size_t bitCount = 0; // count of bits in the buffer

for (float value : data) {

union {

float f;

uint32_t b;

} u = {value};

// pops off n bits

u.b >>= n;

// add the bits to the buffer

bitBuffer |= u.b << bitCount;

bitCount += (sizeof(float) * 8) - n;

// if the bitBuffer contains 8 bits of data, cast it into a byte and add it to the buffer

while (bitCount >= 8) {

// grab last byte from bitBuffer and add it to the buffer

uint64_t bitmask = 0b11111111;

packedData.push_back(static_cast<uint8_t>(bitBuffer & bitmask));

// pop 1 byte off of the bit buffer

bitBuffer >>= 8;

bitCount -= 8;

}

}

// add last byte with packing to the buffer

if (bitCount > 0) {

packedData.push_back(static_cast<uint8_t>(bitBuffer));

}

return packedData;

}

It is important to note that both of these code samples were tested on clang x86_64. Floating point data is not standardized by the c++ ISO and different CPU architectures and compilers can give different outputs as seen here.

It is also important to note that on x86_64, data is stored in memory in the little endian form, meaning that the least significant byte of data is stored first in memory, not last. This means that the order of BYTES (not bits) is reversed in memory, and you will see this if you use std::ofstream to save the data to a file.

Mantissa truncation analysis

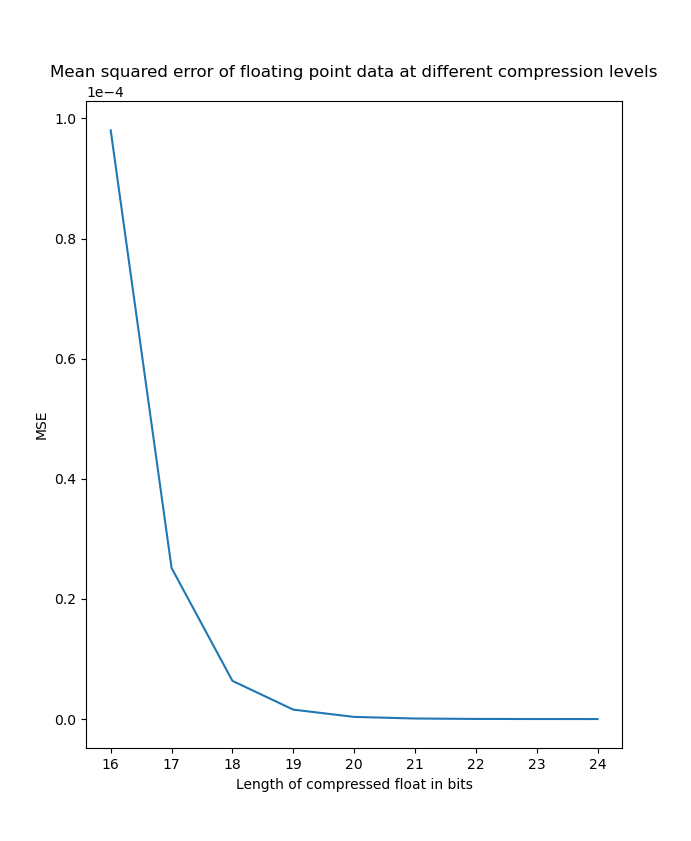

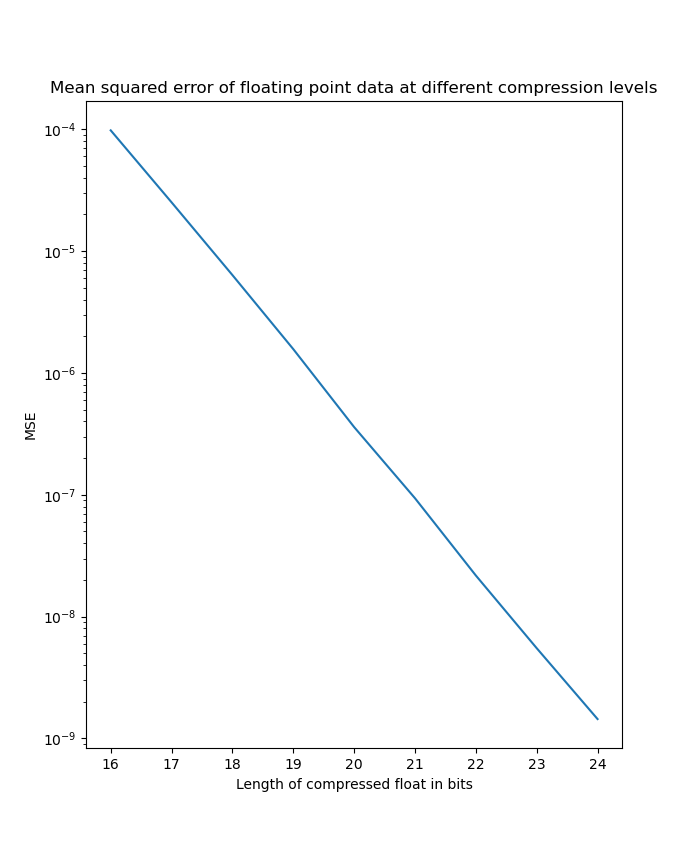

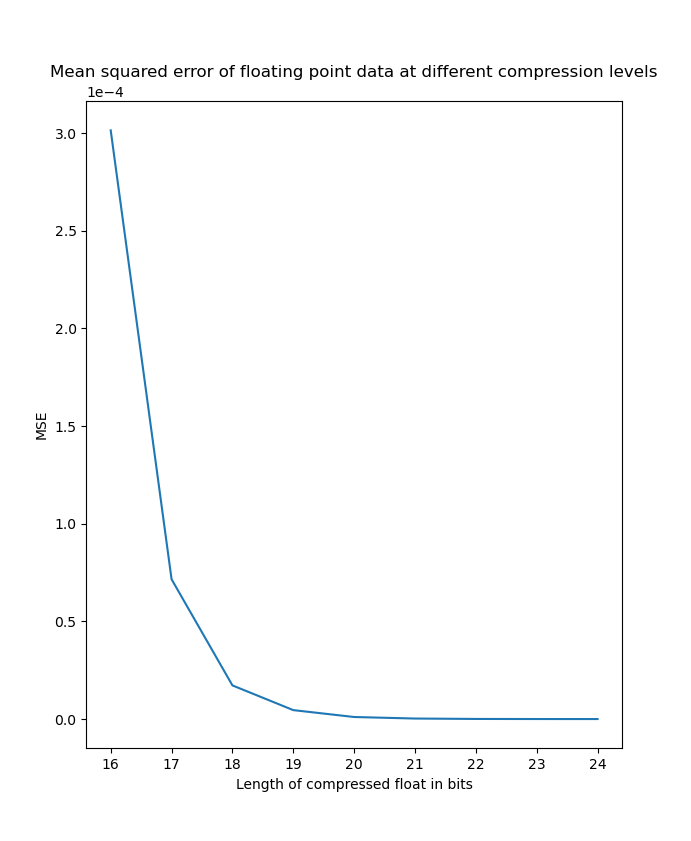

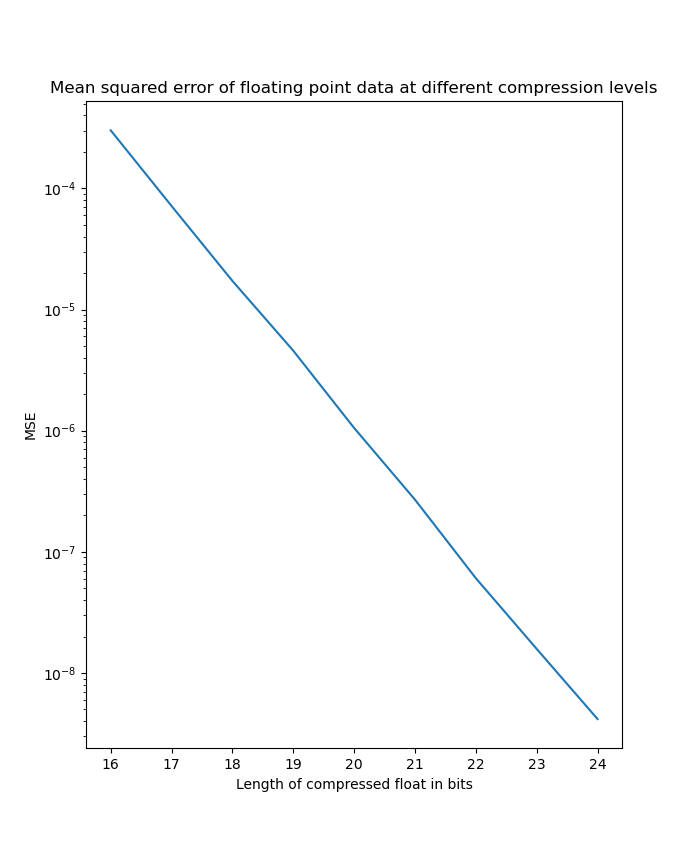

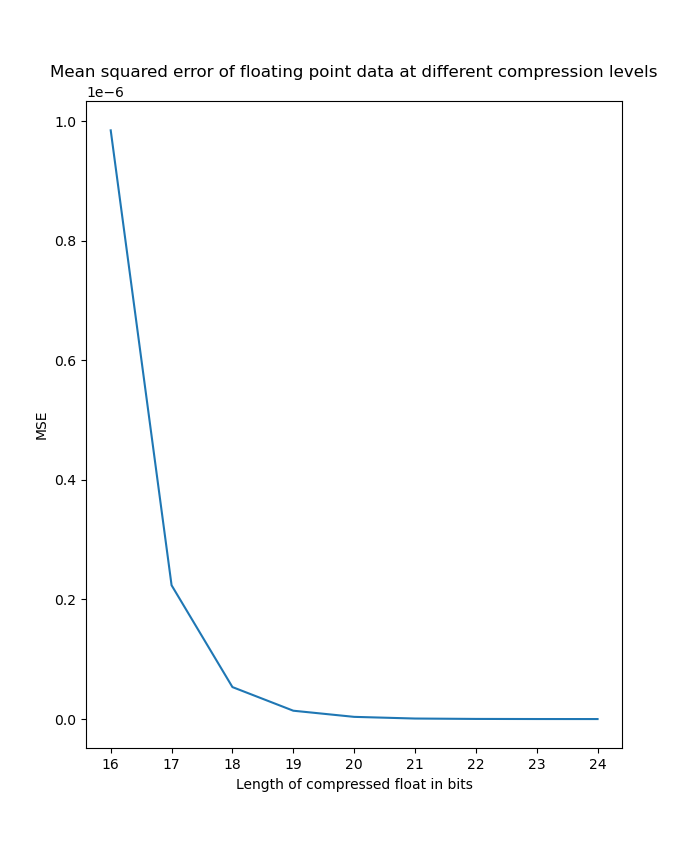

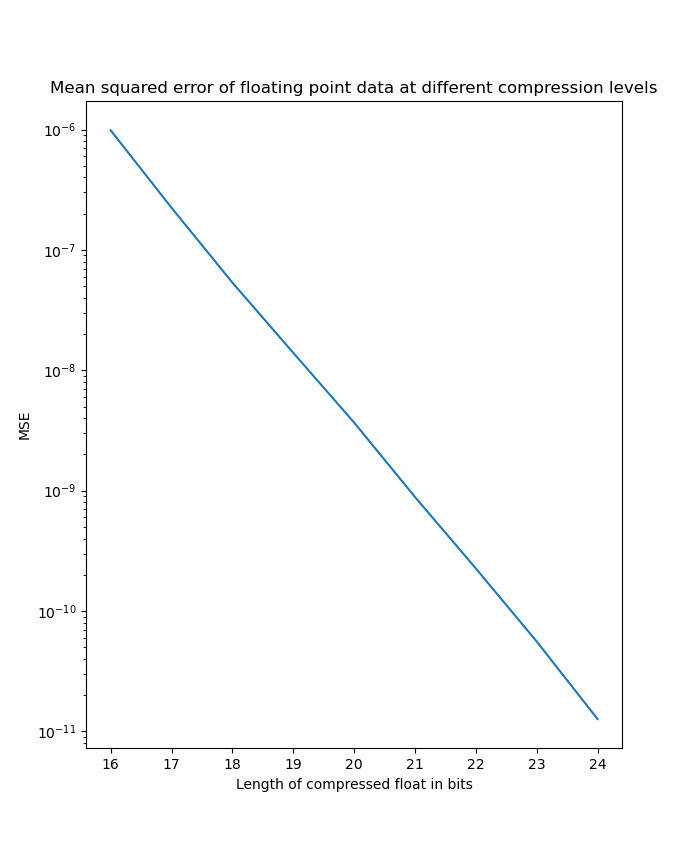

Lets see how much precision we lose from mantissa truncation. I setup a small experiment that generated 500 data points from 3 data distributions, a uniform distribution, normal distribution, and exponential distribution, with these parameters.

std::uniform_real_distribution uniformDistribution{-5.f, 5.f};

std::normal_distribution normalDistribution{0.f, 5.f};

std::exponential_distribution exponentialDistribution{5.f};

Here are the resulting mean squared errors from the compressed data compared against the original data.

| Uniform distribution MSE on linear scale | Uniform distribution MSE on logarithmic scale |

|---|---|

|  |

| Normal distribution MSE on linear scale | Normal distribution MSE on logarithmic scale |

|---|---|

|  |

| Exponential distribution MSE on linear scale | Exponential distribution MSE on logarithmic scale |

|---|---|

|  |

As we can see here, it is very clear that the MSE scales logarithmic with the number of bits we truncate off of the float. At the worst side truncating 16 bits saves 50% of disk space but only introduces an MSE in the order of and at the best side truncating 8 bits only introduces an MSE in the order of . Many applications could benefit from this form of compression and can adjust the level of compression depending on the level of precision needed on an application specific basis.